Driving through Turkmenistan, you look for water more than anything else. Dry, arid land, rich in oil and gas, but covered 80% by the inhospitable and harsh Karakum desert.

Coming from Kyrgyzstan where 94% of the country is mountainous and dotted with alpine lakes and having visited Uzbekistan previously, which boasts of its verdant Fergana Valley, Turkmenistan in comparison was obviously not nature’s favourite child.

To instil the importance of water, the country has assigned the green colour of its flag to be a representation of “new life”. “Without water, there will be no new life; no spring, no new birth,” says my guide alluding to the Zoroastrian beliefs of Nowruz, which was the original religion of Turkmenistan before Islam.

So, when you come by a wedding procession and stop to congratulate the bride and groom, you are gifted the most precious thing you can get: bottles of water.

Entering and exiting Turkmenistan

“Turkmenistan is a crazy country,” I was warned by both Uzbek and Krygyz people prior to arriving here. There are many articles written about its strict rules and surveillance. While much of it has lessened and internet become available (albeit limited), Turkmenistan still remains the most closeted country, which makes its own neighbours – let alone foreigners – wary of its closed-door policy.

In essence, Turkmens are no different from their neighbours – the food is the same, language (except in Tajikistan) has the same Turcic roots, speak Russian as a common official language, follow the same nomadic traditions and have an affinity with Zoroastrian beliefs. Why the secrecy then?

I entered the country by road from the Dashoguz border crossing from Uzbekistan. Passport was checked at least half a dozen times, a PCR test conducted, names verified against the Letter of Intent to travel and then come questions from the border security.

“Do you have any psychotropic drugs, narcotics or prescription medicines you want to declare? Do you have a drone? Do you have any anti-aircraft weaponry?

😳

That was my response to the questions asked by the border patrol. Typically I am asked how long I intend to stay in a country and the purpose of my travel. I answered ‘no’ but couldn’t help smiling; the border patrol smiled back. Of course these are standard protocol questions but they do take you by surprise.

Exiting the country from Ashgabat International Airport was even more painful, extremely bureaucratic and a hugely inefficient process that added a great degree of stress. Unfortunately not the greatest experience for tourists I must say. Having said that, most travellers are not tourists and the locals come with an expectation to encounter delays, scrutiny and questioning.

Darvaza Gas Crater

Once across the land border from Uzbekistan, you enter Daşoguz province. Frankly it feels no different. No hijabs. Men and women interacting freely with one another. Female shop assistants, vendors and an occasional driver. This would have been a porus border before the former U.S.S.R created a boundary and formed Turkmen S.S.R. in 1924.

I chose to eat my lunch in the most Central Asian way as one can imagine: melons with non flat bread and choi (tea) at a roadside vendor. I don’t know what it is about the Stans but their melons are the sweetest in the world, literally dripping of honey-sweet juice.

The radio inside the shack is blaring Lady Gaga’s Alejandro, followed by Adele’s Hello and then David Guetta’s Titanium. It is a little jarring for a country that is so isolated to have such a strong American influence in music. The elderly lady and her daughter struck a conversation with my driver. Obviously I was the topic of their conversation. I eat my lunch taking in their curious glances, giggles and whispers; a foreigner being a rare sight in Daşoguz, before embarking on a 4-hour drive to Darvaza gas crater.

Gas was found in Turkmenistan in the 1940s while oil was discovered as early as the 18th century in the Balkan province near the Caspian Sea.

The 3 things the country proudly proclaims as its main industry are: Black Gold (oil), Blue Gold (gas) and the most surprising of all White Gold (cotton) which is a water-intensive crop that even led to the destruction of Aral Sea next door. In Turkmenistan, petrol is US$ 0.10 cents per litre and a bottle of water, about US$ 0.50 cents for half a litre. Go figure.

The remainder of the trip is on a long road that cuts through the heart of Turkmenistan surrounded by sand, reminding you of countries like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Bahrain.

Turkmenistan, like these oil-rich countries, has gained its wealth from Black and Blue Gold, and has provided its people free education, healthcare, subsidised utilities and built its capital city using white marble from Carrara. Italy. But just like the other former SSR, it too is looking for its identity post independence from the Soviet Union.

Golden horses, red carpets and Turco-Persian origins

Turkmenistan’s National Museum in Ashgabat does a fantastic job of preserving the country’s history, which has curated excavations from the Stone Age up until the Arab conquest. Turkmenistan was the land of nomadic horse breeders who lived in yurts, in search of grazing pastures.

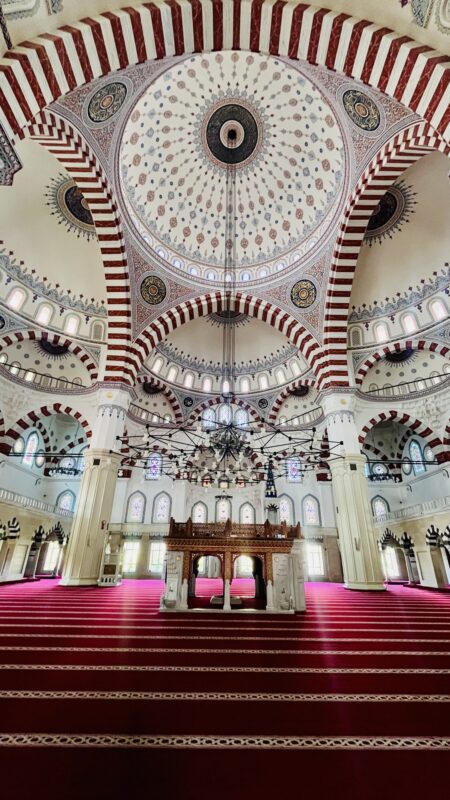

With time, women started to weave carpets with sheep wool which they dyed red using pomegranate skin. Red became associated with Turkmen carpets that also linked with Zoroastrianism’s reverence to the eternal fire.

The earliest example of Turkmen carpet is a 2,500 year old Pazyryk rug that was found in the grave of a Scythian nobleman near the Altai Mountains in Kazakhstan in 1949. It had been very well preserved as it was frozen when it was found. It is currently kept at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia.

With Silk Route flourishing, Turkmen weavers started to sell their carpets in Bukhara, which was a key marketplace. This led Turkmen carpets to be known as Bukhara carpets. The first President of Turkmenistan, Saparmyrat Niyazov, made it his goal for the world to acknowledge Turkmenistan as the origin of carpets.

Turkmenistan even put carpet on its flag; a red vertical band that represents the colour of Turkmen carpets and 5 octagonal “gul” motifs representing its 5 provinces. The country also celebrates “Carpet Day”.

The carpet museum in Ashgabat does a tour to acquaint you of the Turkmen carpets. Once you understand how to interpret carpet motifs, you never go back to only looking for colour and design. Instead, you look for meanings, connection, knots and stories.

The tradition of carpet weaving is a largely female practice, passed down from mother to daughter. Once sheep shearing was done, the wool was handed over to the women to dye and weave.

Men and women had very defined roles and the yurt became a symbol of family for women and protection for men. Its cylindrical wall symbolised eternity. In the centre was the hearth that was associated with family life as well as with Zoroastrianism’s belief in the eternal fire.

From living in yurts, the nomadic tribes rose to create tribal confederations or Khanates. One of the tribal confederations, the Oghuz Turks founded the Turco-Persian Seljuk Empire that were predecessors to the great Ottoman Empire.

The Turkmen were skilled swordsmen and formed military alliances to defend their country against the armies of Alexander the Great, Parthians, Mongols, Arabs and later, the Tsars. In all the battles, the Turkmen swore by a faithful horse as their permanent companion. “We are different from the Kyrgyz; we don’t eat horse meat,” says my guide.

The renowned Akhal Teke horses are a cultural treasure and historic symbol of the desert nomads of Turkmenistan. One the rarest breeds of horses, the gene pool of Turkmen Akhal-Teke horses is being cultivated and carefully preserved.

From humble beginnings in yurts to being the forefathers of the Ottoman Turks who built an empire, the Turkmen are proud of what they have contributed to this world.

If you peer through the crack in the door, you’ll be amazed by the white wonderland it has built in Ashgabat, majestic golden horses, stories about warriors and folklores told through tapestries; there are ancient cities too with citadels and oasis, and even the largest concentration of dinosaur footprints dating back to the Jurassic Period.

Then there’s bazaars filled with caviars, spices, candies and dry fruits; ferris wheels, parks and museums that can keep you engrossed and your camera filled with incredible photos.

They have restaurants serving pizzas and coffees, American music, gaming zones and screens featuring Hollywood films. It doesn’t feel alien or isolated at all; on the contrary, it feels very familiar.

The isolation is a legacy Turkmenistan has inherited from its former leader, something it is trying to shed while trying to protect its identity – an understandable predicament.

There is news, the country wants to open up and make travelling to Turkmenistan easier for tourists.

Visit while that tiny crack is open, while the aura and secrecy is still a part of the adventure. It is no less than the real-life Alice in Wonderland experience.

An absolutely fascinating post Maddie! You have explained so much and definitely shown how interesting this country must be to visit.

Love love love your feedback as always anna. Thank you for reading and appreciating. Hello from Hong Kong. Hope you can visit here 🤞